Author: Jean-Baptiste Waldner

Next book to be published: White Collar Robots and Enterprise 4.0 Management

The business case for a better overall assessment of the transformation

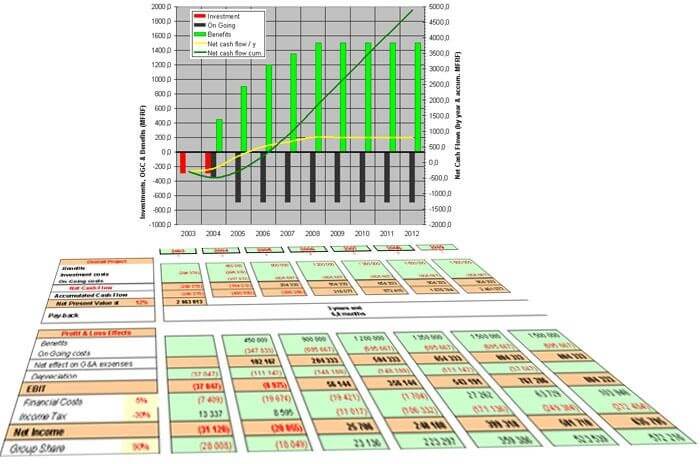

Even today, too many costly transformation programs or technological projects are undertaken without a synthetic, quantitative and objective means of assessing the economic benefits against the costs and risks associated with their implementation.

Digitization programs and other technology-intensive initiatives require substantial investments in hardware, software, services of all kinds and in-house manpower, which must be allocated in line with the expected benefits. What's more, such an evaluation exercise must be carried out over the entire life cycle of the tools, applications, processes and other resources implemented. Finally, the risk factor - the probabilistic notion that dominates this type of initiative - must be carefully integrated into such an analysis.

The business case enables this type of global, quantitative and impartial evaluation. This exercise, often overused by pseudo-ROI analyses, enables us to weigh up the interests of each project's raison d'être, and make a precise choice between the various possible options.

While the business case is best known for its role in assessing a vision and promoting it to justify the allocation of resources, this essential tool is becoming a vital ally when it comes to implementing initiatives. Business cases for transformation programs now have a triple vocation:

- Evaluation of scenarios and strategic options to be implemented (project or program planning and validation)

- Steering the program by expected results, throughout its implementation.

- Post-project verification of implementation of expected value creation (i.e. business case benefits harvesting)

Any initiative aimed at improving service quality must make a measurable contribution to profit. Each stage of the project, each action it requires, must therefore be steered primarily by the expected benefits. Not only must these benefits be identified and quantified in isolation, they must also be reconcilable with the operating account, and objectively accepted.

While a quantitative economic model such as a business case is a matter of course for any decision-maker, two pitfalls generally stand in the way of its successful implementation:

- Estimating benefits is difficult, because many benefits appear intangible at first glance, and so the economic function that governs them appears unquantifiable,

- Costs, which are often the result of a pioneering approach (few similar experiences), are very difficult to establish. When they are, they are subject to a considerable margin of error.

Two abundantly refutable assertions...

First, the estimation of expected benefits. Even when these appear to be non-market in nature, they can still be converted into an economic function. Largely inspired by the foundations of the monetarist doctrine of the 1980s, any act of consumption of a resource is merely an intermediate economic act aimed at creating final satisfaction. It is this final satisfaction that the "profit" economic function models. A singular exercise at first glance, but with a little practice, easily accessible.

On the other hand, the costs of a project are most often obtained through a call for tenders, a quotation of the various services that make up the project. This is a passive approach, in which the calculation effort is passed on to external service providers. However, when these service providers are put out to tender, the aim is to take part in the project by providing a minimum service, which generally increases and multiplies as the project progresses, often under the pretext of incomplete specifications.

The abacus method of cost evaluation...

The principle of abacuses is a radically different option, illustrated by the following comparison: a buyer wishing to build his own house in a given neighborhood has two methods of estimating the cost. The first consists in acquiring a plot of land and then having estimates drawn up for each of the services involved: structural work, roofing, plastering, tiling, electricity, etc. This method will most likely lead to the cost drift mentioned above. A second option is to have the actual construction costs of neighboring houses at your disposal, with their synthetic dimensions: surface area, number of rooms, land area, number of storeys, architectural complexity factor, etc. This is the principle of statistical comparison.

A collection of data relating to similar projects, or where certain factors are similar to those of the project to be implemented, then becomes an essential tool for sizing the solution's investment and operating budgets. These are the abacuses. These abacuses are made up of several input parameters: directly quantitative quantities (number of users, number of sites, number of processes...) and qualitative quantities, allowing the notion of complexity to be integrated (resistance to change, market maturity...). Most major service providers (IT service companies, integrators, telecoms operators, etc.) now use this type of assessment tool, and pass on a risk premium that can be substantial to their customers who do not have an equivalent counter-expertise tool at their disposal.

Costing pioneering initiatives: using formal analogy

When the sector of activity or type of project is truly pioneering, with no previously known equivalent, it is difficult to rely on a sufficiently representative statistical basis to establish a figure.

In this case, the principle of functional analogy is applied: data is drawn from sectors that are similar in some respects. For example, a project to rationalize television chassis was approached in the late 90s using the principles of software-delayed diversification of automobile production lines in the late 1980s. This use of functional analogy also makes it possible to propose, during the scoping study, options that have already been tried and tested in other sectors of industry.

The business case, the arbiter of implementation agility

Implementing a project is a lengthy process, extending over several months, carried out in conjunction with the business activity it is intended to disrupt as little as possible. No plan can infallibly predetermine the events and actions to be prioritized day by day. While an overall plan is essential to organize the phases and major activities of the implementation, the day-to-day organization of tasks must be coordinated flexibly and agilely according to business priorities and other external contingencies.

The neutral and effective arbitration of such agility is based on formal technical and economic criteria. The business case acts as a compass to guide day-to-day priorities. The principles of SCRUM-type agile project management, hitherto applicable exclusively to software development, can now be applied to business transformation initiatives, provided that such a decision-making body is in place to steer the project on the basis of day-to-day results, throughout its implementation.

Checking the initiative's success: benefit harvesting

The last but not least contribution of a business case program is to verify that the initiative has been successfully completed. Checking that the resources allocated have been used effectively. That they have yielded more than they cost.

How can this "harvest" of expected gains be formally organized? For each of the targeted benefits, it's a matter of measuring the level of performance delivered over the course of each quarter or financial year. This means that the initial performance will have been measured when the business case was drawn up, in other words, the initial situation will have been measured. Some gains are immediate, accessible right from the start of the transformation (quick wins, invoicing of discontinued services, etc.), while others are more gradual. Moreover, the indicators used for this measurement will also be corrected for any variations in external influences (market trends, variations in material prices, sales, etc.).

The analysis of results must remain a simple, synthetic but pragmatic exercise to enable a real economic evaluation. The multiplication of initiatives, the experience acquired and the lessons learnt over the years mean that this type of tool can be developed quickly and rationally, and the results can be monitored effectively.

Also read about industry

Industrialization, Scale-up design

Scaling up is the moment when an innovation joins the rest of the company Why create the conditions for success within the company?

Future of industry: understanding and developing industry 4.0

Over the past few years, the media have been talking a lot about the transformation and future of industry known as Industry 4.0. Beyond the concept, it's